Note: This story is also available as a PDF, which you can download and read if you like. I prefer that version, myself.

I have the feeling i used to be able to think but now i can’t because of the house

i think the house had something to do with it, the way we all wandered around that summer, nobody meeting anybody else’s eyes. Nobody talked to me except at breakfast and i don’t know what they all did the rest of the time or in other words i didn’t care. my mother died in may you see and dad packed me off to the lake house like luggage or something and he never met my eyes either.

the house belonged to my grandmother. It was awful. one of those Victorian wooden horrors surrounded by swampland; i don’t know who built it but he was definitely mad and probably had more money than god, not that god would bother to use His money if He had it. anyway the lake was in the middle of nowhere and summer was bad there and winter was worse. the house roof leaked and sagged and there was damp and crusty mirrors everywhere, and viny-tatter curtains and peeling wallpaper and the biggest cobwebs i ever saw and everything the mirrors reflected was always in shadow. For some reason everyone in the family came there in late July and didnt leave till September but my grandmother lived there all year long.

she looked like a fairy tale witch, all bent and beady-eyed, crooked as a broken stair-rail. I remember she used to leave the room and a minute later you’d hear her on the other side of the house. take your eyes off her and she’d be gone. Nobody ever tried to explain that, come to think of it.

she looked like the house, broken and cobwebbed, the skin on her arms like flapping curtains. I avoided her and the house as much as i could cause I thought they were the same really. i avoided everyone else too that summer because as soon as they saw me they remembered my mother was dead and they were supposed to be sorry about it.

[Note that Avoiding is easy when done properly such as taking into account the tallest grass clumps in the area, knowing the best trees to climb, and when Uncle Declan liked to sneak a cigarette. it was even easier because none of my cousins were there that year, Aunt Sandra’s kids were at camp and uncle Declan’s son was in Nova Scotia and pretended not to be unemployed. Obviously they were smart enough to stay away from the lake house. me not so much.]

my grandmother hated everyone there, Aunt Sandra less, but Uncle Declan and Aunt Jennifer most of all. she probably hated my father too, but found it harder at a distance. I would. she hated them for staying away, hated that they pretended to like the house when they did come, hated them for only coming cause none of them wanted to be left out of the will, and because something in their undersized brains went ping! when they heard the word money. my grandmother had a lot of that, which Uncle Declan managed.

he had to tell her what he’d done with the money every summer, she made him give a full report standing up; he did it too, you could see him swallowing and trying to remember breathing techniques but he did it. Then she’d warn him about this and that, and tell him not to be too tricky, not with her money.

Now don’t you go and do anything stupid, she said. I know you. I’m your mother. If you do something stupid I will know.

We won’t stand for it, she’d say. that was one of her favourite phrases. We won’t stand for it. at first I thought it was the royal we, only later i knew that it wasn’t, it was plural, it was her and something else living not dead. nobody really knew that at the time though. we just pretended to understand what she meant, which was probably our first mistake.

The house

I didn’t mean

So summer dragged on and on, the hottest I can remember. my knees were swollen with mosquito bites, and I couldn’t stay too long in the sun or I’d burn and then fry like an egg, or just fry if it was a cloudy day. Aunt Jennifer had brought sunscreen, but it ran out at the beginning of August.

the dark was no relief at night, though. every sound on the lake got sucked up by the house, and the constant echoes chafed at your brain as you lay there, trying to sleep. mosquitoes and blackflies got in through the cracked window glass and flew away swollen. weeds grew up in the night, spreading up the pathway to the house, up against the windows, slumped against the walls. a cracked grey vine had grown up to the roof and died a long time ago, but on nights with a bit of wind it knocked against the glass outside my window, an incessant ticking that made me want to scream. in my mirror, it looked like a long, emaciated hand.

those were the worst nights, because when the wind came the whole house creaked. Floorboards groaned, curtains swept out and across your face, the roof rose and settled like bones shifting.

aunt Jennifer and aunt Sandra had a falling-out of some kind, over what I couldn’t find out, not even by listening behind doors. uncle Declan didn’t say much, but he complained a lot about the bad wi-fi, and had to sneak out to the nearest gas station and buy another pack of cigarettes. Aunt Sandra suspected he’d done it but she hadn’t got any proof (and nobody asked me), so she gave him the cold shoulder, and he had to pretend he didn’t know why, which I guess really stressed him out, because the next time he slunk out to the gas station he went all the way into town and stopped at the pharmacy too. i was pretty sure that bottle wasn’t supposed to be so empty that quickly. then again, nobody ever asked me why he was so twitchy.

my grandmother ate it up. or ignored it. It was hard to tell, only she looked like she was putting on weight but the look on her face never got any less sour. she sat all tense and anticipatory at meals, eating the grown-ups with her eyes, but nothing much ever happened. When I met her in a hallway she always looked surprised that I was there, and otherwise she ignored me.

one day i decided to skip lunch in favour of sitting in a tree near the house, where you could see into the dining room window. There was a crack in the glass so I could hear everything, which was nothing at first, and so I almost dropped off. there was a cicada buzzing in my ear, but I was tired and it was almost soothing after the night before, during which i swear you could hear the weeds crawling up to the house.

and then a plate fell on the table, or someone dropped it, and the next thing I knew uncle Declan was shouting.

It’s the money all the time with you, for God’s sake can’t you think of anything else? I’m the trustee, not your errand boy –

I know damn well what you did, and I say we won’t stand for it, my grandmother said coldly.

You mean you won’t.

The House is displeased.

You’re crazy. I told you, it’s complicated –

I spoke to a lawyer in March.

When did you leave the swamp? What lawyer?

I told you we won’t stand for it, and we won’t.

With that will, you don’t have a choice.

Do you really think that matters? I’m your mother. I know what you did. We won’t -

God, yes! I know!

The door banged, and then everything was silent. nothing happened except for the clink of cutlery, and when I got down to look in the window, aunt Jennifer and my grandmother were eating. aunt Jennifer looked sick, and my grandmother just kept on eating her peas.

I came around the corner of the house and there was Uncle Declan, smoking. he jumped and dropped the cigarette but when he saw it was me he just lit another one. it took three tries.

Well what was that?

What was what?

You know.

Just her again. You know how she is, money this and money that. Stocks, lists, shares.

I didn’t say anything. not that he noticed.

Has to know, can’t be bothered to leave the swamp. You weren’t at lunch.

I had better things to do, I said.

Don’t listen to her. She’s crazy, you know that, right?

So are you, I said, and walked away.

Later i went inside for food on account of being hungry, and came across my grandmother in the hall. she was muttering to herself and I sort of edged past her quietly, or tried to because she grabbed my arm instead.

Always saying no. Always saying you don’t understand, and does it matter anyway.

Uh-huh, I said.

Thinks I can’t hear. should be deaf by now, about time. Snake. Snake, but mine. Don’t displease the House, she said, and I was pretty sure she meant me.

Sorry?

Whichever one you are. I’m sure you will. Always saying no, when really, it means the opposite, or will, since we’re clever.

Then she let go of my arm and wandered off. In a second i heard her footsteps in the upstairs bathroom, on the other side of the house.

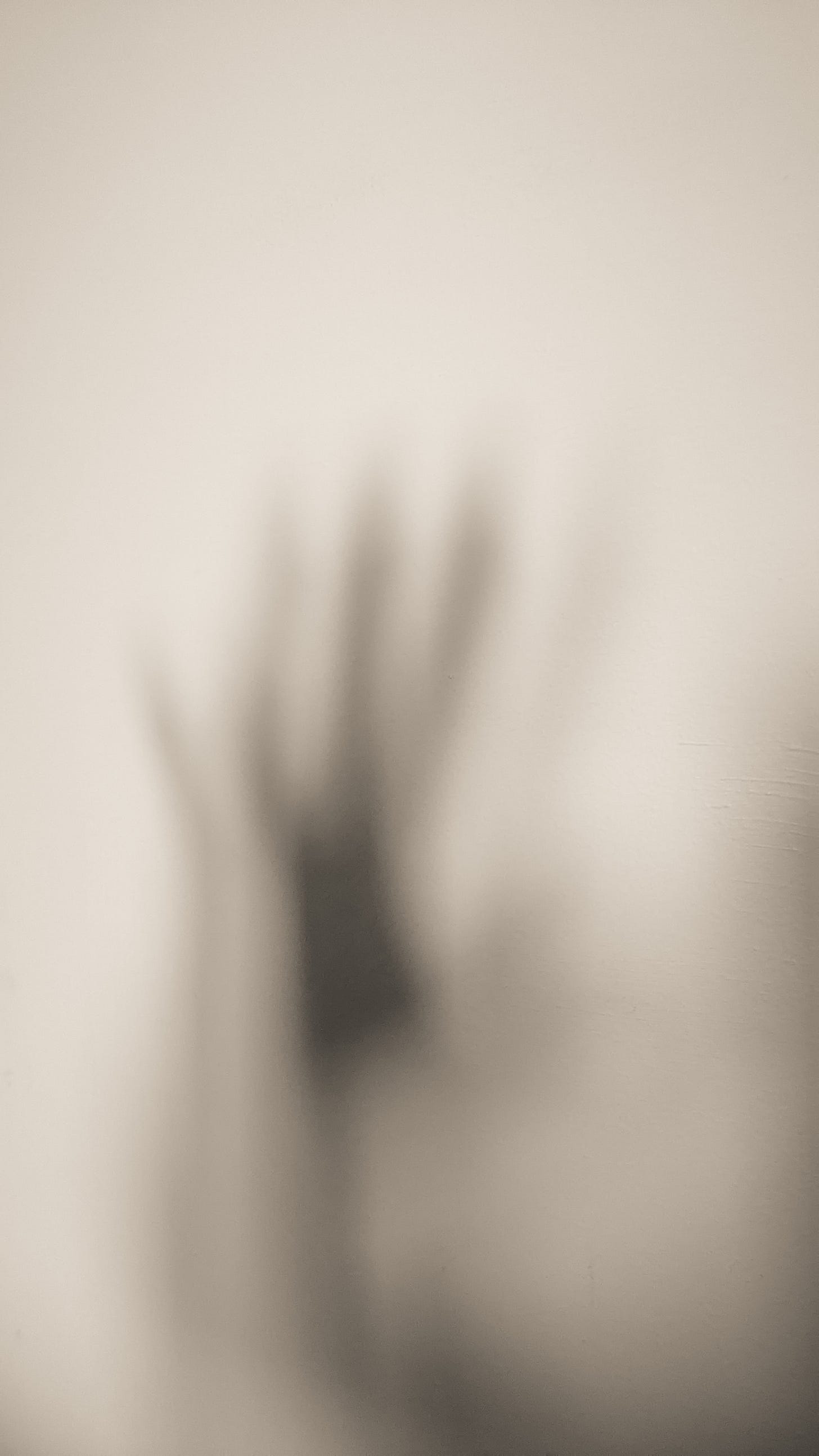

something in the hallway mirror, like a hand, caught my eye, but I ignored it.

And all this I know can’t be enough to explain why i found myself on the side of the road the next night, walking in any direction but the one I knew id come from, and it doesnt explain why the wind felt like cold fingers, and that cold fingers were the best thing id ever felt in my life, there, staring at the bone-sliver moon through the pines

but I can’t say why, though i never promised anything, and that’s all.

or

i woke in the night, terrified by my shadow rising to meet me in the mirror across the room. then i had a dream.

The moon was white

bone-slivered, pale

and I heard the sound of groaning, or growing. so

Iwent downstairs

down eachstaircreakingandsighing

and found something

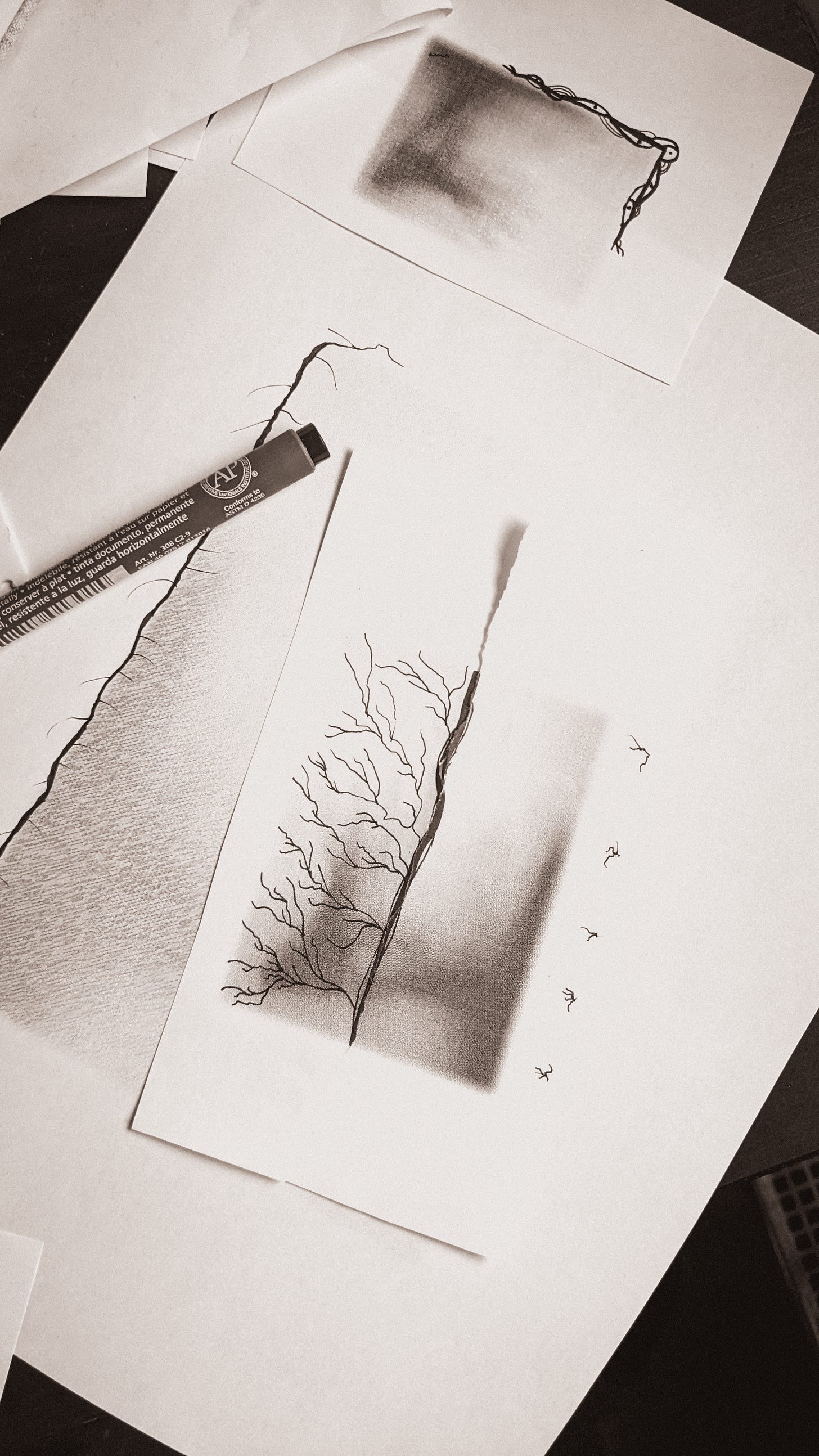

growing through the hall, a tracery of vines, black-flowered, limp, cold to the touch. I followed this to the dining room and found the table set for twenty places, all the chairs pulled out. but the cushions on the chairs were made of coiled weeds, Queen Anne’s lace and goldenrod and milkweed, and the walls were strung with morning glory, the leaves yellow and heat-withered.

and the tablewas set

for sixteen people who were not there

who had never been there

but uncleDeclanandauntSandraandauntJennifer were there

uncle Declan looking very nice in oak leaves and the ladies in willow

and all their bodies were wrapped in vines like snakes, living vines half-decayed, coiling up and into their mouths, and they waited and swallowed and jerked their heads back and smiled I think

and my grandmother sat at the head of the table in black lace like a ghost, tendrils of vine in her eyes and ears, singing

and then as I was watching she smiled at me

with a thorn-tipped finger to her lips,

and wrenched back her head with a sickening crack, and a tree grew from her mouth

its crown piercing the roof

and its branches the walls

and in the room it sounded like a summer night

played by an orchestra

Saying yes, yes, yes, and I will know

and i ran out of the house and down the lane and into the road, and as I did the wind rose and came to meet me, passing up and over me, and truly there is nothing more for me to say to you

because god knows that if there’s anything our family can’t do it’s hear no, we have to whisper to it, twist it, rendering it as boneless as an eel. we can’t lose, and i think that I have lost.

I never went back. three weeks later someone delivered a package to the house and found it all fallen in, the vines growing over it. my leaving was written off as teenage moods, and nobody ever asked me any questions.

when I imagine telling you this, as anything other than a dream, I see my shadow in the mirror, just a hand at first, barely a shape. and then it grows, then it’s me, my face, eyes closed and smiling, and there is a ribbon woven of weeds and tattered lace over my lips. so it hardly matters because whatever I have won I don’t truly have, and most certainly have lost, because I promised – by living, and not promising at all – that I wouldnt displease the House.

because the hand in the mirror is mine. not-mine. Mine.

and so theres nothing more I can tell you/

What I love most here is how the horror isn’t just “a haunted house,” but the way a family lineage becomes architecture. The rot is generational, the grief is structural, and the house doesn’t just shape the narrator—it finishes her sentences. The tone feels like a girl realizing she was raised inside something hungry, something older than the grandmother, older than the swamp, older than language. And the ending lands with that perfect kind of folkloric ambiguity: she escapes, technically, but the house keeps her anyway.